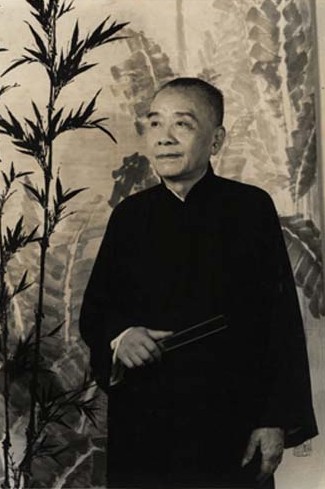

MA SHOU-HUA(1893-1977)

MA Shou-hua, also known as Mu-xuan or Xiao-jing, was a native of Guo-yang County, Anhui Province. He was born in the 19th year of the reign of Emperor Guanxu of the Qing Dynasty (1893) and died in the 66th year of the Republic of China (1977) at the age of 85. He had two painting studios; one was called Zi-kuan Studio and another one was called Xiao-jing Study. He also called himself “Master of Xiao-jing Study”.

He was one of the earliest judges of the Republic of China and throughout his official career held various positions including many judgeships at different levels of the courts, Secretary General of Capital Nanjing, Government Member and Finance Director General of the Taiwan Provincial Government, Chairman of the Land Bank, and then was elevated to be Secretary General of the Judicial Yuan, Chairman of the Administrative Court, Chairman of the Committee on the Discipline of Public Functionaries, etc.

Mr. Ma loved painting since he was little and had studied calligraphy and painting ever since as a hobby, especially exerted intensive study of the paintings of Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing Dynasties. He came out to be a very well-established and influential calligrapher and painter. He was Chairman of the China Artists Association, Chairman of the China Calligraphy Society, Committee-Member-in-Charge of the China Painting Society. He also commanded lots of respects in the Japanese calligraphy and painting community.

All in all, he was a reputable calligrapher and painter, art educator, jurist, and highly regarded as “Judicial Patriarch”, and “Revitalizer of the Chinese Traditional Ink Painting” in Taiwan.

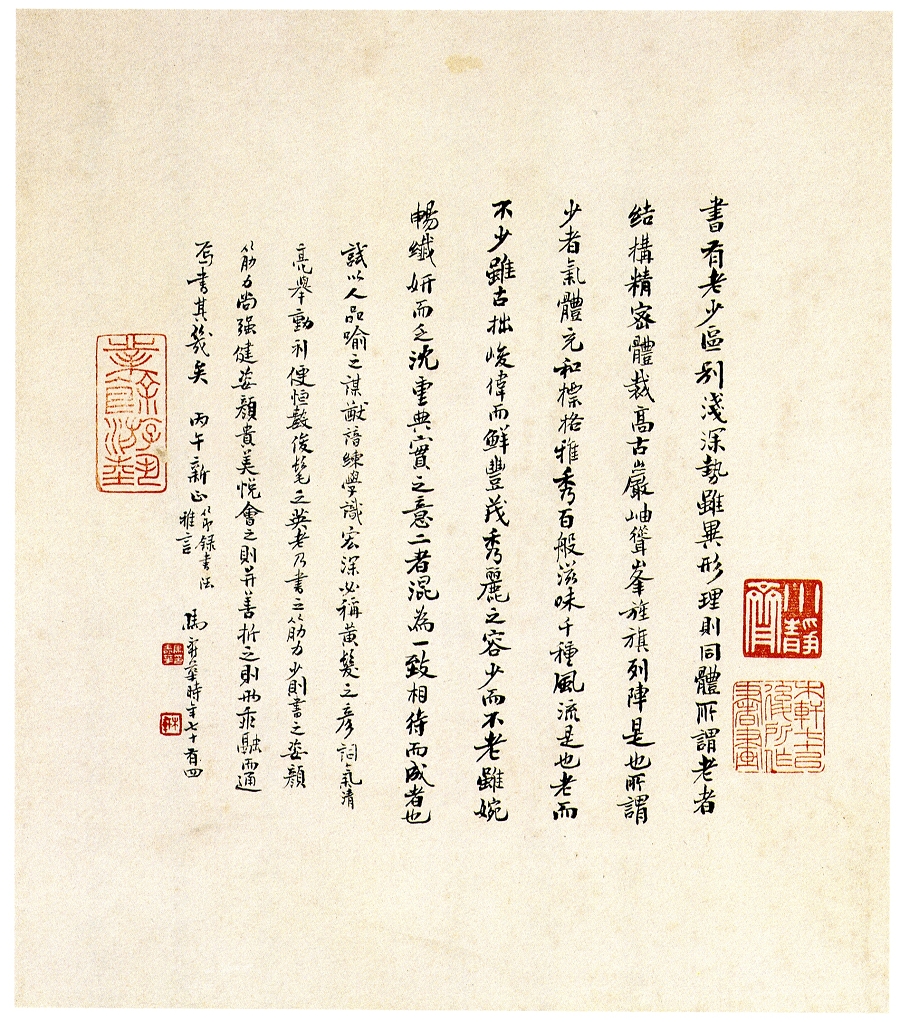

Excerpts from “Elegant Words on Calligraphy,” in Running Script

This calligraphy work is excerpts from Elegant Words on Calligraphy by Xiang Mu, a critique on calligraphy from the Ming dynasty. This piece in running scripts is neat and concise, the brushstrokes are restrained yet lustrous. Two calligraphy sizes are included here: the bigger is seen in the first half of the work and the smaller in the second. One may tell the artist’s profound capability in calligraphy by the work’s sophisticated hues of ink and its fine composition.

It indicates Mr. Ma’s keen perception of the meaning behind the texts that he has put an ancient critique in his own work. The writing is upright, sincere, cautious and steady—which derives from his life-learning attitude of investigation and endurance. The calligrapher was already 74 at the time, yet he still transcribed these precepts unceasingly, sought for excellence everyday, and did not cease learning even at his stage of accomplishment. Hence the endeavor demonstrates the modest, humble and virtuous character of this master of his time. (Texts by Chiang You-wen)

Title: Excerpts from “Elegant Words on Calligraphy,” in Running Script

Year: 1966

Size: 24x27cm, album

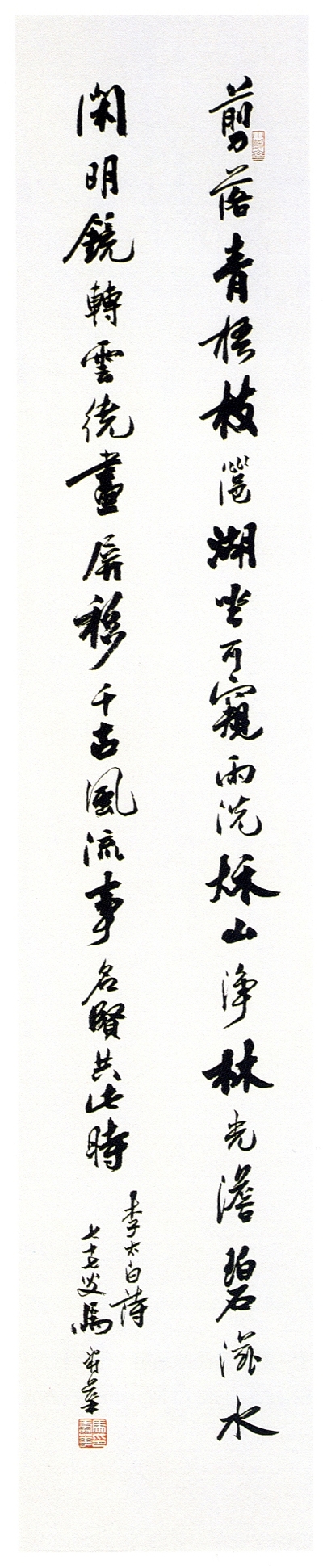

Poem by Li Bai in Running Script

This piece in running script is an excerpt of Li Bai’s poem. There are just 40 characters spreading on the wide sheet of paper, which demonstrates the calligrapher’s perfect mastery of the entire layout without giving the audience an impression of emptiness. Every character seems to have unique features—the size, the spacing and the hue of ink—none of the them is identical, yet all within the calligrapher’s intentional design. Besides bringing a variety of flavors in the work, these features also express the natural, unrestrained attitude of the poem—hence the piece is well liked by its audience and one’s mind flows with the tempo of its calligraphy as one appreciates it. (Texts by Wang Yu-jing)

Title: Poem by Li Bai in Running Script

Year: 1969

Size: 117x23cm, hanging scroll

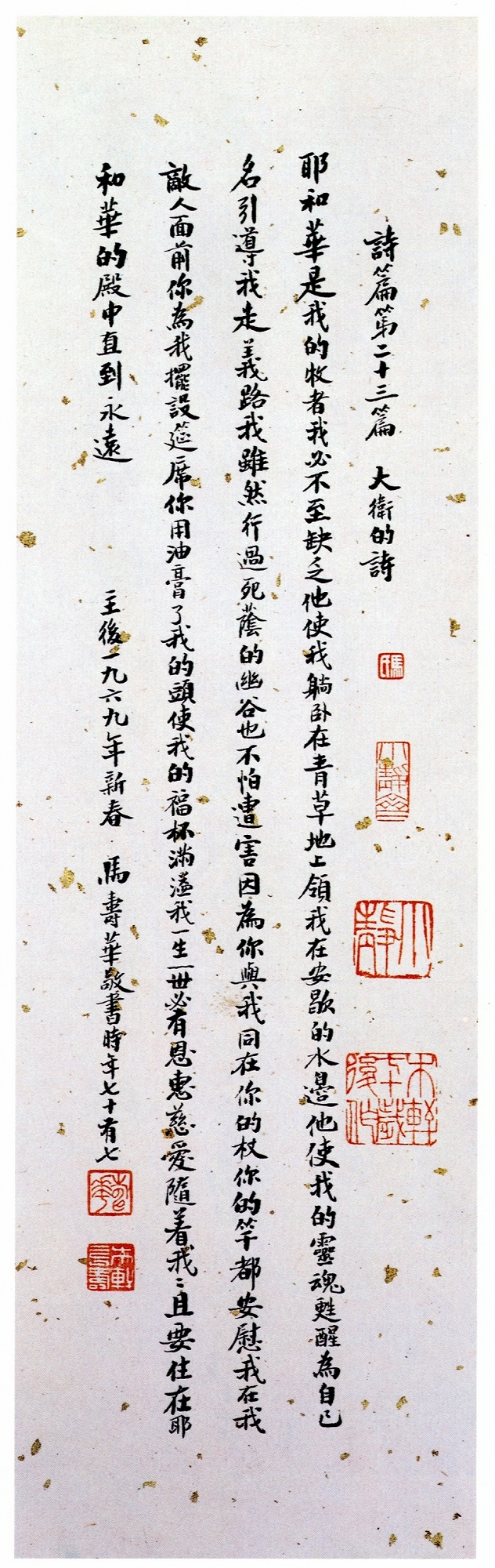

Psalm 23 in Regular Script

At 63, Ma Shou-Hua was baptized along with his wife, and became the vice-chairman of the Council Committee of The Bible Society in Taiwan. Mr. Ma had once ordinated a calligraphy group exhibition of Bible verses, and invited Christian calligraphy-lovers and master calligraphers to communicate the Gospel of God via scripture, as well as proclaiming the artistry of Chinese calligraphy. This piece presents a psalm of David, composed in regular script. Apart from Ma’s other regular script works, each character’s strokes are neat, the spacing is tight, and together this work has a well-restrained tone while every line overflows with his conviction and respect to his own religion. Additionally, the calligrapher chose to write on a paper fabric which is decorated with gold leaves—an endeavor which signifies his devout intention to glorify God. (Texts by Wang Yu-Jing)

Title: Psalm 23 in Regular Script

Year: 1971

Size: 43x13cm, hanging scroll

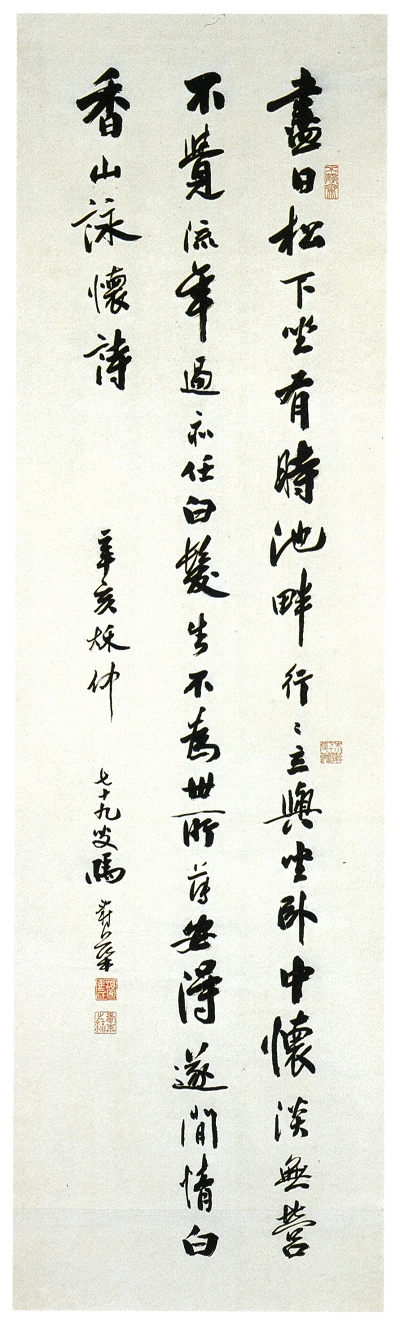

Poem by Bai Juyi in Running Script

The work features a poem by Bai Juyi, in running script with a thick writing. As the size of each character varies from another distinctly, this work displays an easygoing, nonchalant writing attitude. From the first line one may discover the variety of writings, from thick to thin, in each character, bringing forth a visual sense of rhythm. The spacing between lines is orderly and consistent, and though the running script is written at a swift pace, yet the calligrapher maintained a regular, consistent spacing in the overall layout and did not lose the order. (Texts by Li Si-Jie)

Title: Poem by Bai Juyi in Running Script

Year: 1971

Size: 154x44cm, hanging scroll

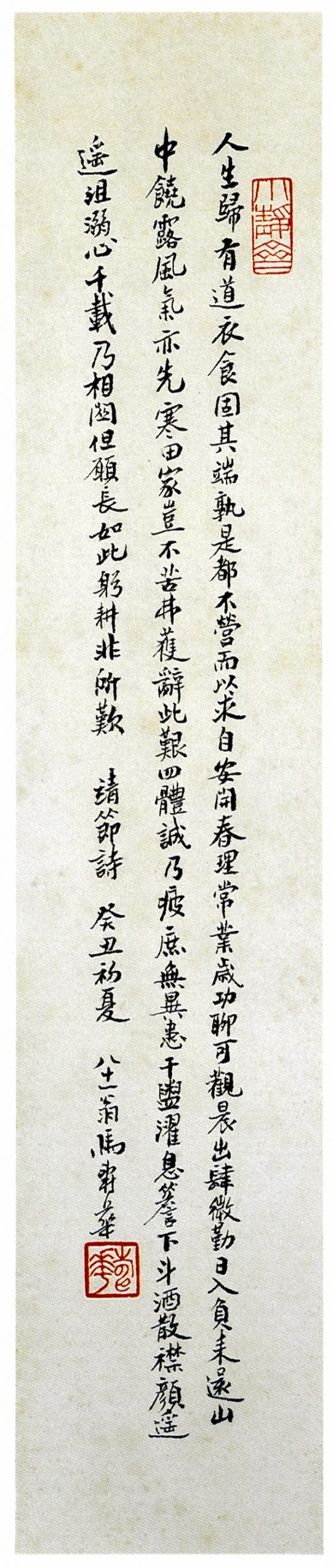

Poems by Tao Qian in Regular Script

This work consists of a poem by Tao Qian. The overall layout structure is fairly steady, and the spacing tight and even. At the first line the center Qi slightly leans to the left—the top 4 characters are right at the middle while the following 5 start to cling to the left thus creating a curve which leans toward the left; from the second line, the center Qi comes back to the middle by degrees and hence presents an orderly vibe in the writing. A series of exquisite variations is found in its balanced structure: the highlighted slant strokes—such as “Shi”, “Chen” and “Yen”—are expanded intentionally, in an attentive technique. The horizontal strokes slightly lean towards the upper right corner, such as “Yi” and “Han”—influenced by Huang Tingjian’s writing style of calligraphy; and the hook strokes are constructed with well-balanced rising, pressing and twists… These characteristics in the calligraphy show the cautious writing attitude of their creator. (Texts by Lee Yi-Mei)

Title: Poems by Tao Qian in Regular Script

Year: 1973

Size: 36 × 7.5 cm

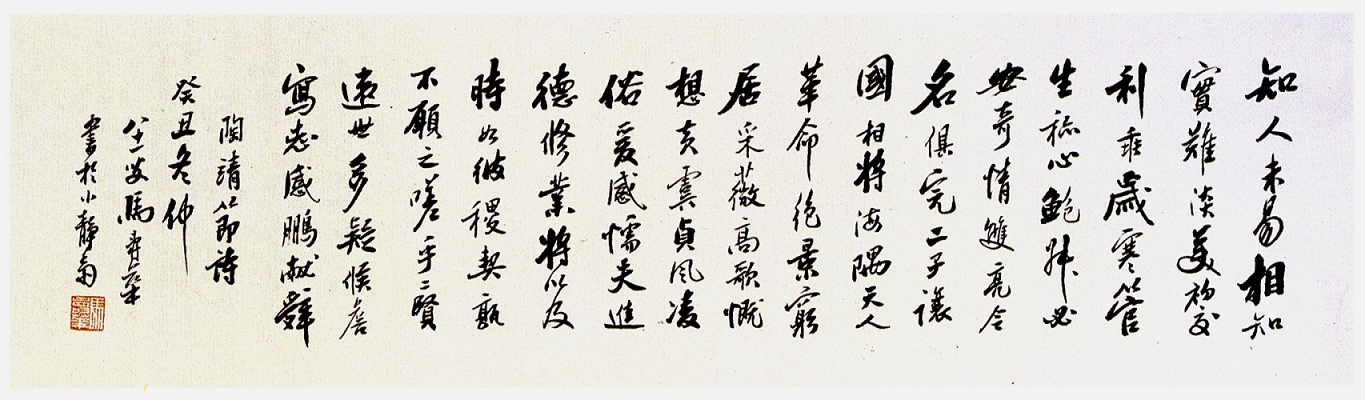

Poems by Wang Wei in Running Script

As a 4-in-1 piece which takes the form of 4 horizontal scrolls, this work has Wang Wei’s 6 poems scribed—its content communicates the calligrapher’s peaceful, leisurely state in his later years via the scenes expressed by Wang Wei’s poems. Overall, the writing is round, solid, smooth and without any sharp points either at the beginning or the end of the strokes, for example the character “Nan”. Regarding his application of ink, sometimes the calligrapher wrote with dense black ink and thus created a weighty sense of calmness in the form of written characters, such as “Zhong”, “Shi” and “Song”. At other times he wrote in a delicate, thin writing yet without creating any flaky impressions, such as the vertical strokes of “Shui” and “Jiang” and thus constructed a tense contrast in the picture by the differed writing styles. Sometimes he applied diluted ink in order to create a sense of simplicity in certain characters, such as ”Chu”, “Zhu” and “Gu”; and sometimes, he intentionally creates the flying white(Fei Bo) effect by using a dry brush, which can be seen in “Zhou” and “Tao”. This, has indicated the calligrapher’s efforts on the layout. (Texts by Lee Yi-Mei)

Poems by Wang Wei in Running Script

Year: 1973

Size: 134 × 34 cm, hanging scroll

Title: Poems by Tao Qian in Running Script

Taking the form of a horizontal scroll, this work recites 3 poems by Tau Yuan-ming—Kuang Bao, Yi Qi and Chu Jia. The center Qi in this work mostly leans to the left side, except for the last line where it is in the middle. The top character in each line was written with dense, black ink, coupled with series of various following characters, which together create a harmonious outcome. What stands out about this work is the intentional expansion of the left side strokes—seen in several characters such as “Ming”, “Zhu” and “Fu”, with the latter character even indicates a writing movement of back-hook in the end. The calligrapher also wrote the vertical strokes of several characters with the brush tip, such as “Shu” and “Ming”—which has presented his serene, peaceful attitude. (Texts by Lee Yi-Mei)

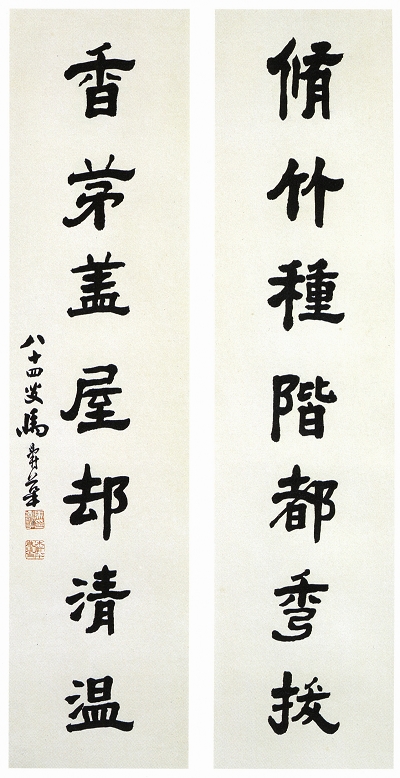

Couplet in Clerical Script

Ma Shou-Hua’s clerical script is solemn but not featureless, steady, yet not dull. Each of the horizontal strokes starts with a slightly downward-angled silkworm head, then at its end, its tail rises with a perfect angle—the overall aura is formal and restrained, yet does not lack gracefulness. The structure of calligraphy is unpretentious, as its method of writing roams between the thickness of bridle, dismemberment and the exquisiteness of horsewhip and pecking. Although written in clerical script, this work contains an exquisite, powerful energy and the charm of variation.(Texts by Yang Ya-Pei)

Title: Couplet in Clerical Script

Year: 1976

Size: 106 × 25.5 cm, hanging couplet

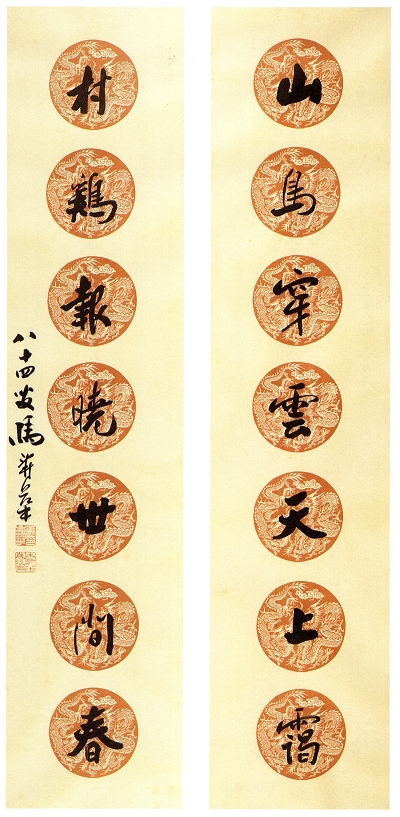

Couplet in Running Script

The writing of Chinese characters in this work varies between two extremes: an extremely vigorous one and an extremely light one. The former is constructed densely, as if several lines can embody a strong force; the latter consists of slim and graceful strokes, all connected in Flying White script without any pauses. Ma Shou-Hua’s running script very rarely shows sharp points, and this entire work is natural, elegant and unrestrained within a subtle, refined style. (Texts by Yang Ya-Pei)

Title: Couplet in Running Script

Size: 100 × 23 cm, hanging couplet

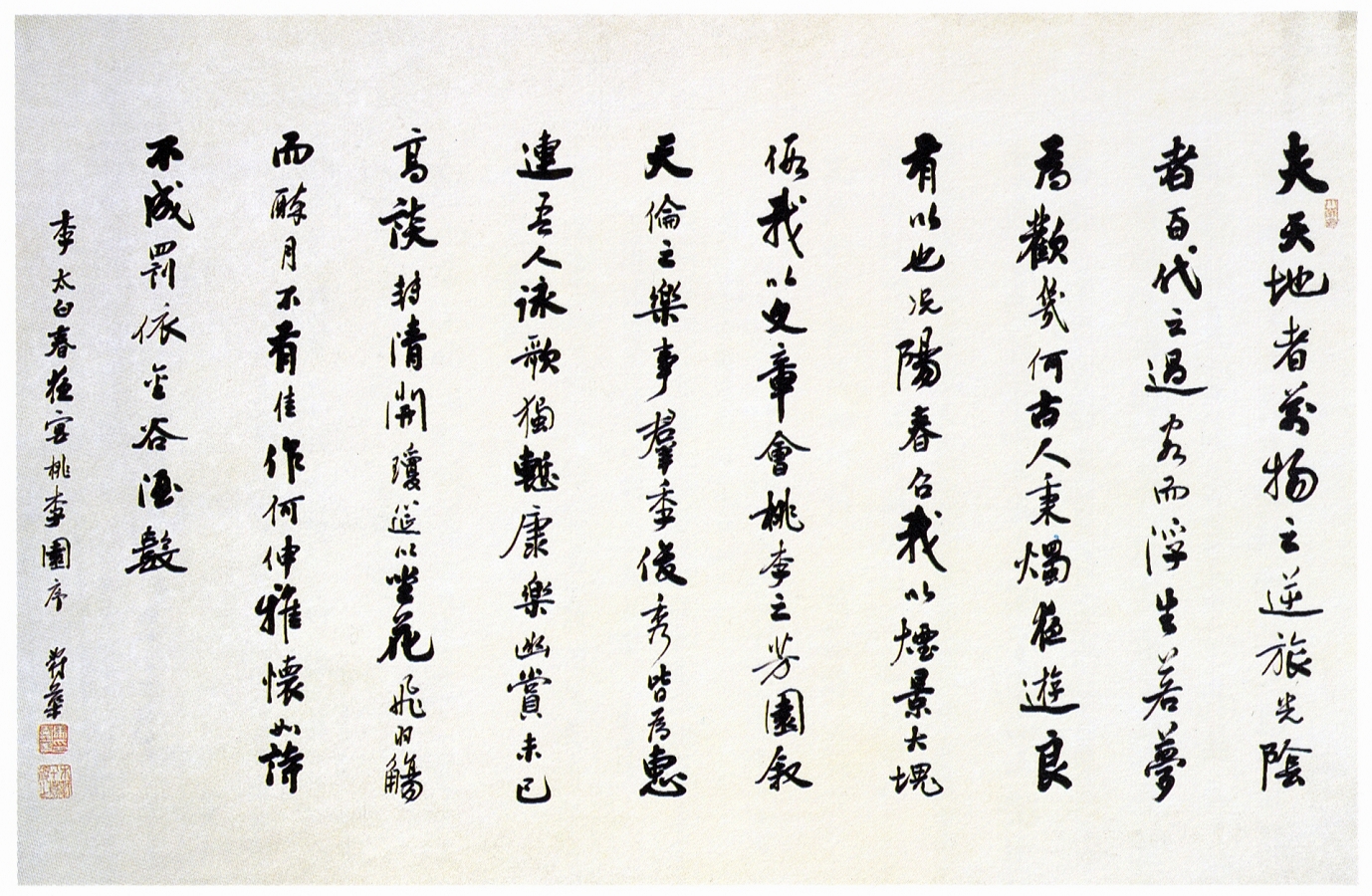

Li Bai’s “Preface to a Night Banquet in an Orchard of Peach and Plum” in Running Script

This poem by Li Bai(701-762), the great Tang dynasty poet, is a well-recognized work. While comprising only 119 Chinese characters, yet it has been deemed “Excellent in its sentence structure, beautiful in every expression” by later generations. Its content indicates a perception that the world is like a fleeting dream and that one had better seek pleasures and live in the moment. Here Ma Shou-Hua’s running script is mainly done in a thick, round writing, and the arrangement of the moist, dense, dark ink displays a rich yet graceful atmosphere, while its spacing is sophisticated, elegant, clear and wide. The calligrapher chose to employ moist ink with a heavy writing on the first character, “Fu”—an initiating filler word—which brings forth a powerful momentum of the poem at its opening, and additionally expresses the intensity of the poet’s emotions. For the grand words like “the heaven and the earth”, “all beings”, “a hundred generations”, the calligrapher wrote in a weighty, vigorous style; other words such as “spring day”, “peaches” and ”drunken moon” are presented in a slim, flying white writing, demonstrating an aura of elegance. The exquisite overall layout under the calligrapher’s design reads with a flavor, which makes its audience linger around and become absorbed in the calligraphy—captivated by its vision and its tone. (Texts by Chiang You-wen)

Translation of the title: by Thomas E. Smith and Fang-mei Chou

Video